Removing Barriers to Healthy Cities

How Collaborative, Technology-Enabled Solutions Can Dismantle Barriers to Community Health and Wellness

We define

healthy cities in terms of community goals and outcomes that illuminate

concrete needs, barriers, and solution opportunities.

Imagine a

community where one can rise for an early morning jog, stop at the local

grocery store for coffee and fruit, pop into the neighborhood health clinic to

check on a persistent cough, then make way via bus, train or bike to a

well-paying job not more than twenty minutes away. This community has adequate

affordable housing, diverse and sustainable employment, and accessible and

reliable transportation. Its residents feel safe and have access to current and

emerging technology, quality education, physical activity, nutrition, and, of

course, adequate health care.

This example

is illustrative of many measures of a “healthy” community; but, for many residents,

such can only be imagined.

Systemic disparities and biases create significant barriers to achieving health and wellness for all communities.

Communities that struggle to obtain or maintain key elements of a healthy community require targeted resources and efficient solution deployment to address deficiencies. From Seattle, to Chicago, to New York[1] many cities have acknowledged that what underpins historical lack of success in building, maintaining, and supporting healthy communities is a reluctance to acknowledge and address systemic disparities and biases caused by issues such as racism and gender inequality. Many municipalities, philanthropic organizations, and local community organizations provide services and resources to address the resulting symptoms of these inequities; however, healthy communities cannot emerge until we remove the barriers that keep residents from accessing those resources and keep communities entwined in racism, gender inequality, and other systemic issues.

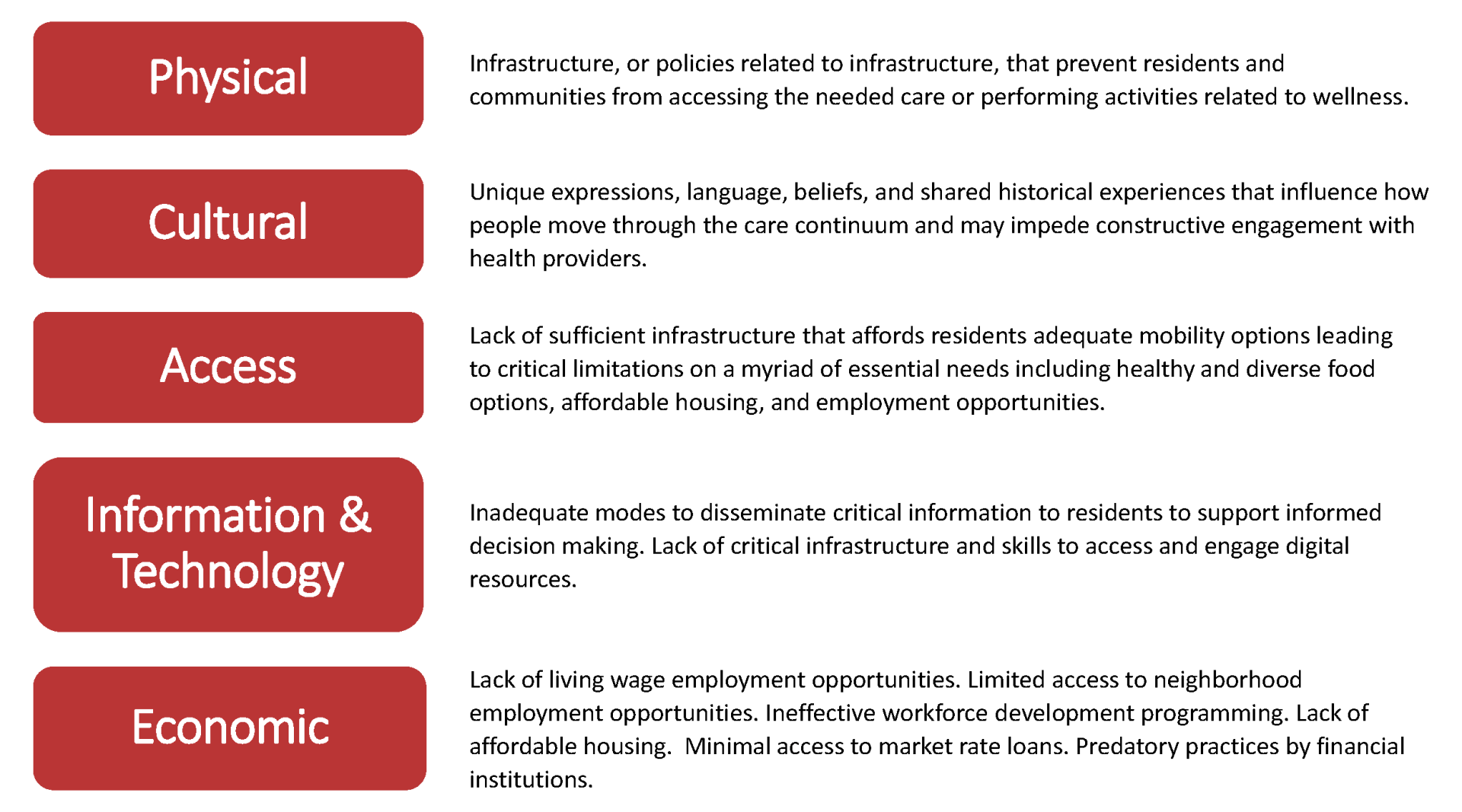

Physical, digital, and socioeconomic barriers impede healthy communities.

There are numerous ways to categorize barriers that impede a community’s ability to obtain and maximize resources to eliminate systemic disparities and equities. Below is a structure to help identify the barriers, define them, and then develop sustainable solutions to address each.

Developing and deploying solutions for healthy cities will require structured collaboration, standardized data, and technology to capture, track, and scale impact. Solutions that address physical, digital and socioeconomic barriers will broaden the impact of future efforts.

Complex Problems Require Collaboration

COVID-19 has

highlighted the devastating and disparate impact health crises have on

vulnerable communities. At the same time, the pandemic has inspired a renewed

focus on pledging resources to those communities. As efforts evolve, community

stakeholders must be mindful of the strength and success of coordinated

solution development and deployment as opposed to fragmented support or duplicated

efforts. Complex problems that span neighborhoods, entities, and municipalities

cannot be solved alone.

To create

healthy cities, we must first collaborate to effectively design and deploy

technology-enabled solutions that redress health inequities. Grass roots

organizations are closest to the pain of their communities and know the

immediate and sustained needs of that community; philanthropic organizations

have access to data and funding; thought leaders have the benefit of deep

analysis; technology partners have the platforms that can be leveraged and

scaled; and cities want their residents to be happy and healthy. Cross-sector

collaboration brings together expertise, insight, and representation across all

stakeholders, ensures that the right problems are being address, and leads to better

design and implementation of sustainable solutions.

Using

Data to Understand Impact

Solving

health inequities requires implementation of holistic, sustainable solutions

that remove barriers and allow for stakeholders to effectively redress root causes

of those inequities. Problems as complex as workforce development, food and

housing insecurity, and internet and technology access span systems,

jurisdictions, and service providers; current lack of data standards across

systems makes it difficult to truly understand the impact of current and future

solutions. However, expansive data analytics of health indicators would allow

philanthropic groups, community organizations, and cities to see correlations

and downstream impact early on. We must measure health through broad lenses

that capture both the root causes and related symptoms to truly understand

inequities and the impact of targeted solutions.

Technology

is Key to Sustainability

Technology

can play a critical role in collecting and monitoring data as well as solving

specific problems related to health inequities. Having the data that supports health

disparities is but one component of understanding how to address the issues

that restrict equitable positive health outcomes throughout urban environments.

Technology

solutions allow dynamic and creative responses to complex problems. Technology

also holds the ability to replicate and scale solutions so they can apply to an

array of challenges. Whether incorporating new urban design aspects (such as flexible

design of streets), advanced analytics (including machine learning, data

science, and artificial intelligence), or sensing networks (nodes in our

environment that collect and communicate data), technology will be a critical

component in developing sustainable solutions that can be scaled to other uses

and cities.

For example, City

Tech’s Urban Heat Responsesolution integrated NASA Landsat

data on climate and weather data to improve design and infrastructure to

mitigate urban heat islands. The outcome was a user-centric tool leveraging

environmental data to identify hot spots for further analysis, test the effects

of city interventions designed to reduce heat, and create a baseline for future

urban planning.

It is

crucial that these technologies be developed and implemented while applying a

racial equity lens to ensure they do not create more biases and reinforce

existing barriers.

Healthy cities are achievable if we work together.

No one can

thrive while racial, social, and economic injustice prevent everyone from

contributing to and benefiting from a city’s success. Many organizations are

already addressing symptoms of these injustices and working towards a healthier

community. However, before we can truly address root causes, we must first

remove the barriers that prevent communities from even accessing these

resources in the first place. Data and technology will play an essential part

creating equitable, sustainable, and scalable solutions for healthy communities

– but only if we can work together.

-----

[1] Chicago, New York,

Seattle, Minneapolis, Madison, and Portland are among American cities that have

launched racial equity initiative to address systemic structural issues

underpinning poverty, health, unemployment, etc.

About the Author:

Angela E.L. Barnes serves as the General Counsel and Director of Legal

Affairs & Growth Initiatives for City Tech Collaborative. City Tech is a nonprofit urban solutions

accelerator that tackles problems too big for any single sector or organization

to solve alone. Working with cross-sector teams, City Tech develops scalable,

technology-enabled solutions to make cities happier, healthier, and more

productive. In her role, Angela handles all legal matters and provides

strategic leadership for the company’s growth. Angela is co-leading City Tech’s

racial equity and inclusion framework and she is also spearheading City Tech’s

Healthy Cities Initiative which will address multidimensional barriers facing

communities that struggle to achieve positive health outcomes, ultimately

producing and deploying a data analytics tool accessible to community

organizations, governments, and other community health stakeholders.

Angela is a

passionate advocate for providing services and resources to underserved

geographic and demographic communities has extensive. Her non-profit board

service includes, current Board Chair for the Center on Halsted, former

Co-Chair of the GLAAD Chicago Leadership Council, former Board Chair for SGA

Youth & Family Services, former Board Chair for Chicago Coalition for the

Homeless (current Executive Committee member). Angela co-founded SHE100, a

philanthropic giving circle of lesbian and queer women supporting organizations

throughout Chicago. She also leads the Women’s Action Council at the Center on

Halsted focused on outreach and inclusion of the queer women’s community in

Chicago.

Angela was

awarded her Juris Doctor from Columbia University and Bachelor of Arts from

Wellesley College. She is a Certified Compliance and Ethics Professional (CCEP)

and a member of the Society of Corporate Compliance and Ethics (SCCE).